India’s bureaucracy; Power, corruption, and the system that holds it back

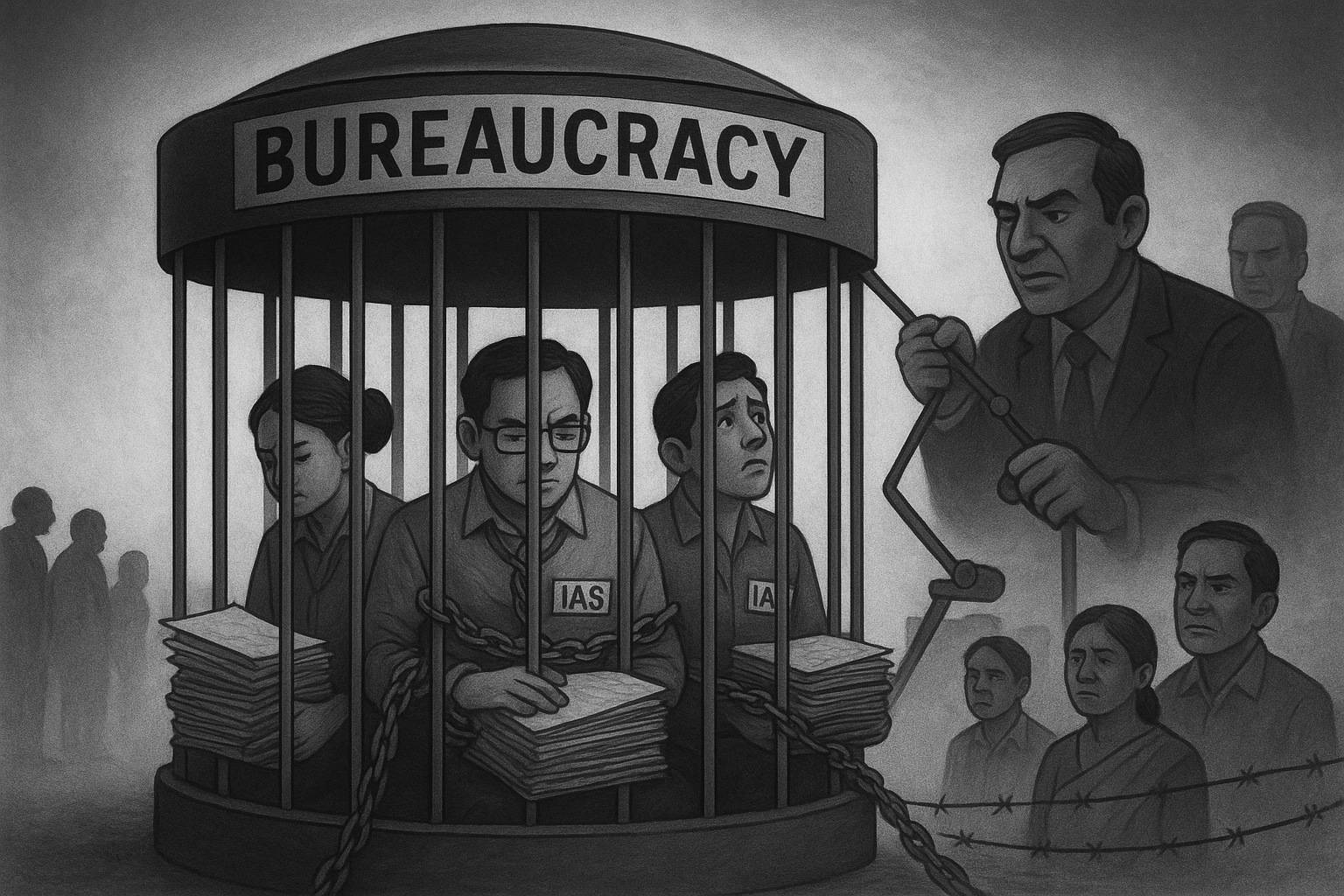

India’s bureaucracy is often called the “steel frame” of the nation, entrusted with implementing policies, delivering public services, and ensuring government schemes reach the people. Yet, despite its size and influence, the system is riddled with contradictions. While some officers are lauded for their dedication, others face accusations of corruption, and many capable officers find their work stifled by transfers, paperwork, and political interference. The result is a paradox: a powerful institution that, too often, struggles to serve the citizens it was designed to help.

This paradox is visible in the contrasting careers of individual officers. In 2000, Pooja Singhal became India’s youngest IAS officer at just 21 years and 7 days (Wikipedia, 2025). Her early postings reflected promise and merit: as a Subdivisional Officer in Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, she conducted raids on godowns illegally selling Jharkhand Shiksha Pariyojana books and carried out the state’s first survey of physically challenged citizens. These achievements earned her a posting as Officer on Special Duty to Jharkhand’s Chief Secretary in 2014, and by 2021, she became the Secretary of the Mines and Industries Department.

Yet, in 2022, Singhal’s career took a dramatic turn. The Enforcement Directorate (ED) raided her properties in a money laundering investigation , accusing her of diverting Rs. 19 crores from the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) scheme into her and her relatives’ accounts. To conceal the funds, she allegedly established 50 shell companies that invested around Rs. 100 crores into Pulse, a luxury hospital owned by her husband. Her assets, reportedly worth Rs. 82 crores, were raided, and the Supreme Court rejected her bail , highlighting the case’s severity (OpIndia, 2025; Wikipedia, 2025).

Singhal’s story underscores a broader problem: corruption is only part of the challenge. India’s bureaucracy is constrained by systemic inefficiencies, political interference, and a culture that prioritizes survival over service. Between 2016 and 2019, the government received around 2,500 complaints against civil servants, yet only two IAS officers were dismissed for corruption (Hindustan Times, 2019).

Consider the Noida land scam between 2008 and 2014. Nearly 80% of commercial land in 12 villages was allocated to three real estate groups at artificially low prices, allowing builders to profit crores while taxpayers bore the cost (CAG Report, 2021). Similarly, in Haryana, Ashok Khemka, a 1990-batch IAS officer, investigated land deals involving Robert Vadra’s company Skylight Hospitality and DLF Universal Ltd. Khemka found that Vadra’s company bought land for Rs. 75 crore and sold it shortly after for Rs. 580 million, a sevenfold profit. Despite the evidence, political intervention led to Khemka’s transfer , exemplifying the risks faced by upright officers (Financial Express, 2012).

The system itself discourages sustained reform. IAS officers typically serve just 464 days (around 15 months) in a posting , rotating across unrelated departments (Government Data, 2019). This “transfer raj” prevents them from fully understanding their roles or implementing lasting change. Proactive officers, like Divya Mittal, 2013-batch IAS and District Magistrate of Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh , show what could be achieved. Under the Har Ghar Jal scheme , she provided tap water to Lahoriya Da village, which previously relied on tankers. Yet, she was transferred shortly after the project’s success , a move attributed to local political pressure (Financial Express, 2023).

The bureaucracy also suffers from “kagaz raj,” an obsession with paperwork inherited from British administration. Nayanika Mathur, an anthropologist, notes how district officers prioritize signing files over engaging with citizens (Mathur, Paper Tiger, 2015). In Madhya Pradesh, a school improvement program failed because teachers spent hours on paperwork rather than teaching students. Economist Karthik Muldidharan observes that even motivated officers are stifled by juniors who resist change, waiting for transfers rather than supporting innovation (Muldidharan, 2019).

Structural deficiencies amplify these problems. India has only 16 government employees per 1,000 citizens , compared to far higher ratios in countries like China or the U.S. (World Population Review, 2023). Around 10 lakh government positions remain vacant , according to Union Minister Jitendra Singh (Hindustan Times, 2023). Filling these vacancies has a demonstrable multiplier effect: research shows that hiring judges in district courts accelerates case resolution, freeing assets and boosting local economic activity (World Bank Study, 2019). Similarly, effective officers in education, public health, or rural development can create far-reaching positive outcomes—but only if allowed to work without constant interference.

The incentive structure for government employees compounds the issue. Salaries are determined by seniority rather than performance. Teachers’ pay does not reflect student outcomes , while government doctors and nurses often earn more than their private-sector peers (ILO Study, 2015; Comparative Study, 2017). This limits motivation to innovate, while risk-averse behavior dominates. Officers learn that the safest course is to avoid controversy, ensure no fraud occurs in their immediate work, and wait for transfers.

Political priorities often exacerbate systemic inertia. Many elected leaders focus on quick, vote-winning schemes, such as subsidies, rather than long-term reforms. In Punjab, 22% of the state’s revenue is spent on farmer electricity subsidies , contributing to groundwater depletion (Punjab State Finance Report, 2022). Programs that could train and educate farmers for more sustainable practices are neglected because results take years to manifest. Politicians, focused on the next election cycle, prefer initiatives that show immediate voter impact.

This combination of factors creates a paradox: India’s bureaucracy is powerful in theory but constrained in practice. Officers like Pooja Singhal highlight the risks of corruption, while officers like Ashok Khemka, Divya Mittal, and Nayanika Mathur demonstrate how systemic constraints hinder good governance. Despite being part of a “steel frame,” as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel described, civil servants often operate in what German sociologist Max Weber called an “iron cage”, trapped by procedure, transfers, and political oversight.

Several solutions are possible. Fixed tenures of three to five years for senior positions could give officers the security and continuity required to implement meaningful reforms. Performance-linked incentives, such as rewarding teachers for improved student outcomes or officers for development projects completed, could align bureaucratic priorities with citizen welfare. Filling vacant government positions would create significant multiplier effects for the economy, governance, and social development.

Ultimately, reforming India’s bureaucracy is crucial not only to curb corruption but also to unlock the civil service’s potential. Without addressing structural flaws, paperwork burdens, short tenures, and political interference, even the most capable officers cannot achieve lasting change. For India to move forward, the bureaucracy must be empowered to act decisively, held accountable transparently, and structured to reward performance over mere seniority. Only then can the “steel frame” live up to its promise of strengthening governance rather than perpetuating systemic inertia.